RubyMotion Runtime Guide for iOS and OS X

The RubyMotion runtimes implement the Ruby language functionality required during the execution of an application. The object model, built-in classes, and memory management system are part of the runtime.

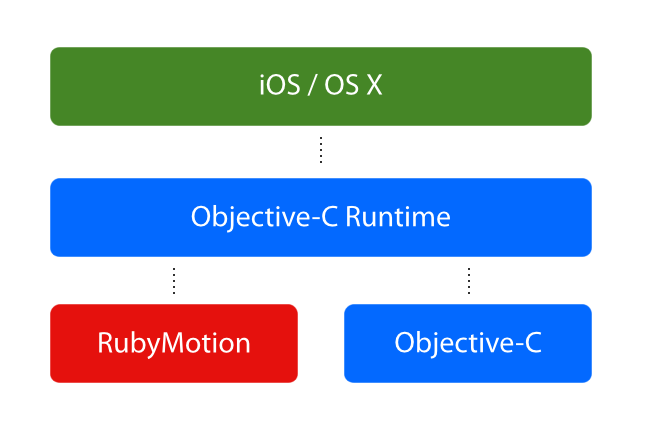

RubyMotion comes with a runtime for iOS and OS X, based on the Objective-C runtime and core Cocoa classes.

Although similar in appearance, this RubyMotion runtime has a completely different implementation than CRuby, the mainstream implementation (which is also called MRI, or simply Ruby). We will cover the main differences in the following sections.

The key feature of the RubyMotion runtime is its tight integration with the Objective-C runtime, which makes it suitable for use on power efficient devices as well as for writing performance-intensive code.

RubyMotion follows the Ruby 1.9 language specifications.

1. Object Model

The object model of RubyMotion is based on Objective-C, the underlying language runtime of the iOS and OS X SDK. Objective-C is an object-oriented flavor of C that has been, like Ruby, heavily influenced by the Smalltalk language.

Sharing a common ancestor, the object models of Ruby and Objective-C are conceptually similar. For instance, both languages have the notion of open classes, single inheritance and single dynamic message dispatch.

RubyMotion implements the Ruby object model by using the Objective-C runtime, the library that powers the Objective-C language and indirectly, the iOS SDK APIs.

In RubyMotion, Ruby classes, methods and objects are Objective-C classes, methods and objects respectively. The converse is also true. Objective-C classes, methods and objects are available in Ruby as if they were native.

By sharing the same object model infrastructure, Objective-C and RubyMotion APIs can be interchangeable at no additional performance expense.

1.1. Objective-C Messages

RubyMotion lets you send and define Objective-C messages.

An Objective-C message, also called a selector, can look different than a typical Ruby message, if it contains more than one argument.

Unlike Ruby messages, Objective-C messages contain keywords. Each argument has a keyword associated to it and the final Objective-C message is the combination of all keywords.

Let’s take the following piece of Objective-C code which draws a string.

[string drawAtPoint:point withFont:font];In this code, string, point and font are variables. The message keywords are drawAtPoint: and withFont:. The complete message is the combination of these keywords, drawAtPoint:withFont: , which is sent to the string object, passing the point and font objects as arguments.

Objective-C messages can be sent from RubyMotion using a similar syntax.

string.drawAtPoint(point, withFont:font)It is important to keep in mind that the message being sent here is drawAtPoint:withFont:. To illustrate more, the same message can be manually dispatched using the send method.

string.send(:'drawAtPoint:withFont:', point, font)Objective-C messages can also be defined in RubyMotion. Let’s imagine we are building a class that should act as a proxy for our drawing code. The following piece of code defines the drawAtPoint:withFont: message on the DrawingProxy class.

class DrawingProxy

def drawAtPoint(point, withFont:font)

@str.drawAtPoint(point, withFont:font)

end

end|

Tip

|

The syntax used to define Objective-C selectors was added to RubyMotion and is not part of the Ruby standard. |

1.2. Objective-C Interfaces

As Objective-C is the main language used to describe the iOS SDK, it is necessary to understand how to read Objective-C interfaces and how to use them from Ruby.

Objective-C interfaces can be found in Apple’s iOS API reference and also in the iOS framework header (.h) files.

An Objective-C interface starts with either the minus or plus character, which is used to respectively declare instance or class methods.

For example, the following interface declares the foo instance method on the Foo class.

@class Foo

- (id)foo;

@endThe next one declares the foo class method on the same class.

@class Foo

+ (id)foo;

@end|

Note

|

(id) is the type information. Types are covered in an upcoming section, so you can omit them for now.

|

As seen in the previous section, arguments in Objective-C methods can be named with a keyword. The sum of all keywords form the message name, or selector.

The following interface declares the sharedInstanceWithObject:andObject: class method on the Test class.

@class Test

+ (id)sharedInstanceWithObject:(id)obj1 andObject:(id)obj2;

@endThis method can be called from Ruby like this.

# obj1 and obj2 are variables for the arguments.

instance = Test.sharedInstanceWithObject(obj1, andObject:obj2)1.3. Selector Shortcuts

The RubyMotion runtime provides convenience shortcuts for certain Objective-C selectors.

| Selector | Shortcut |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

As an example, the setHidden: and isHidden methods of UIView can be called by using the hidden= and hidden? shortcuts.

view.hidden = true unless view.hidden?1.4. Super

In Objective-C, super sends a message to the superclass of the current class, invoking a specific method. In the example below, super would send the play message to MediaController with song as the argument.

@interface VideoController : MediaController

@end

@implementation VideoController

- (void)play:(NSString *)song {

[super play:song];

// Customize here...

}

@endIn Ruby (and by extension, RubyMotion), super sends a message to the superclass of the current class, invoking a method of the same name and passing it the same arguments.

class VideoController < MediaController

def play(song)

super

# Customize here...

end

endIn Objective-C it is possible to call a method on the super class and bypass the method locally. This is especially convenient when defining init methods.

@interface CustomView : UIView

@property (copy) NSString *text;

@end

@implementation CustomView

- (id) initWithFrame:(CGRect)frame {

[super initWithFrame:frame];

self.text = @"";

return self;

}

- (id) initWithText:(NSString*)text {

UIFont *font = [UIFont systemFontOfSize:12];

CGRect size = [text sizeWithFont:font];

// skip local initializer

[super initWithFrame:CGMakeRect(0, 0, size.width, size.height)];

self.text = text;

return self;

}This is a contrived example because in this case it would be fine to call initWithFrame. But there are cases where you do not want to call your local method, but you need to call the method on super.

This is not easily accomplished in Ruby (see How do I call a super class method on stack overflow). In Ruby you need to alias the parent method and call that method instead.

class CustomView < UIView

alias :'super_initWithFrame:' :'initWithFrame:'

# if your method takes multiple arguments, you can alias that as well

# alias :'renameWithArg1:arg2' :'methodWithArg1:arg2'

def initWithFrame(frame)

super.tap do

@text = ''

end

end

def initWithText(text)

font = UIFont.systemFontOfSize(12)

size = text.sizeWithFont(font)

super_initWithFrame([[0, 0], size]).tap do

@text = text

end

end

end2. Builtin Classes

Some of the built-in classes of RubyMotion are based on the Foundation framework, the base layer of iOS and OS X.

The Foundation framework is an Objective-C framework, but due to the fact that RubyMotion is based on the Objective-C runtime, the classes that it defines can be naturally re-used in RubyMotion.

Foundation class names typically start with the NS prefix, which arguably stands for NeXTSTEP, the system for which the framework was originally built.

Foundation comes with the root object class, NSObject, as well as a set of primitive object classes. In RubyMotion, Object is an alias to NSObject, making NSObject the root class of all Ruby classes. Also, some of the built-in classes inherit from Foundation types.

Here is a table showing the ancestors chain of a newly created class, Hello, as well as some of the Ruby built-in classes.

A direct consequence of hosting the Ruby built-in classes on Foundation is that instances respond to more messages. For instance, the NSString class defines the uppercaseString method. Since the String class is a subclass of NSString, strings created in Ruby also respond to that method.

'hello'.uppercaseString # => 'HELLO'Conversely, the Ruby interface of these built-in classes is implemented on their Foundation counterparts. For example, Array’s `each method is implemented on NSArray. This allows primitive types to always respond to the same interface, regardless of where they come from. each will always work on all arrays.

def iterate(ary)

ary.each { |x| p x }

end

iterate [42]

iterate NSArray.arrayWithObject(42)But the main purpose of this design is to allow the exchange of primitive types between Objective-C and Ruby at no performance cost, since they don’t have to be converted. This is important as most of the types that will be exchanged in a typical application are likely going to be built-in types. A String object created in Ruby can have its memory address passed as the argument of an Objective-C method that expects an NSString.

2.1. Mutability

The Foundation framework ships a set of classes that have both mutable and immutable variants. Mutable objects can be modified, while immutable objects cannot.

Immutable Foundation types in RubyMotion behave like frozen objects (objects which received the freeze message).

As an example, changing the content of an NSString is prohibited and an exception will be raised by the system if doing so. However, it is possible to change the content of an NSMutableString instance.

NSString.new.strip! # raises RuntimeError: can't modify frozen/immutable string

NSMutableString.new.strip! # worksStrings created in RubyMotion inherit from NSMutableString, so they can be modified by default. The same goes for arrays and hashes.

However, you must be aware that it is very common for iOS SDK APIs to return immutable types. In these cases, the dup or mutableCopy messages can be sent to the object in order to get a mutable version of it, that can be modified later on.

3. Interfacing with C

You do not need to be a C programmer in order to use RubyMotion. However, some understanding of basic notions explained in this section will be required.

Objective-C is a superset of the C language. Objective-C methods can therefore accept and return C types.

Also, while Objective-C is the main programming language used in the iOS SDK, some frameworks are only available in C APIs.

RubyMotion comes with an interface that allows Ruby to deal with the C part of APIs.

3.1. Basic Types

C, and indirectly Objective-C, has a set of basic types. It is common in iOS SDK APIs to accept or return these types.

An example are the following methods of NSFileHandle, which both respectively accept and return the C integer type, int.

- (id)initWithFileDescriptor:(int)fd;

- (int)fileDescriptor;Basic C types cannot be created from Ruby directly, but are automatically converted from and to equivalent Ruby types.

The following piece of code uses the two NSFileHandle methods described above. The first one, initWithFileDescriptor:, is called by passing a Fixnum. The second one, fileDescriptor, is called and a Fixnum is returned back to Ruby.

handle = NSFileHandle.alloc.initWithFileDescriptor(2)

handle.fileDescriptor # => 2This table describes all basic C types and discusses how they are converted from and to Ruby types.

| C Type | From Ruby to C | From C to Ruby |

|---|---|---|

|

If the object is |

Either |

|

||

|

If the object is a |

Either a |

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

If the object is a |

A |

|

When using an API that returns the void C type, RubyMotion will return nil.

3.2. Structures

C structures are mapped to classes in RubyMotion. Structures can be created in Ruby and passed to APIs expecting C structures. Similarly, APIs returning C structures will return an instance of the appropriate structure class.

A structure class has an accessor method for each field of the C structure it wraps.

As an example, the following piece of code creates a CGPoint structure, sets its x and y fields, then passes it to the drawAtPoint:withFont: method.

pt = CGPoint.new

pt.x = 100

pt.y = 200

'Hello'.drawAtPoint(pt, withFont: font)It is possible to pass the field values directly to the constructor.

pt = CGPoint.new(100, 200)

'Hello'.drawAtPoint(pt, withFont: font)RubyMotion will also accept arrays as a convenience. They must contain the same number and type of objects expected in the structure.

'Hello'.drawAtPoint([100, 200], withFont: font)3.3. Enumerations and Constants

C enumerations and constants are mapped as constants of the Object class.

For instance, both NSNotFound and CGRectNull, respectively an enumeration and a constant defined by Foundation, can be directly accessed.

if ary.indexOfObject(obj) == NSNotFound

# ...

end

# ...

view = UIView.alloc.initWithFrame(CGRectNull)|

Important

|

Some enumerations or constants defined in the iOS and OS X SDK may start with a lower-case letter, like kCLLocationAccuracyBest (starting with k). Because Ruby constants must always start with a capital letter, their names must be corrected by changing the case of the first letter, becoming KCLLocationAccuracyBest (starting with K) in Ruby.

|

locationManager.desiredAccuracy = kCLLocationAccuracyBest # NameError: undefined local variable or method

locationManager.desiredAccuracy = KCLLocationAccuracyBest # works3.4. Functions

C functions are available as methods of the Object class. Inline functions, which are implemented in the framework header files are also supported.

As an example, the CGPointMake function can be used in Ruby to create a CGRect structure.

pt = CGPointMake(100, 200)

'Hello'.drawAtPoint(pt, withFont: font)|

Important

|

Most functions in the iOS and OS X SDK start by a capital letter. For those who accept no argument, it is important to explicitly use parentheses when calling them, in order to avoid the expression to be evaluated as a constant lookup. |

NSHomeDirectory # NameError: uninitialized constant NSHomeDirectory

NSHomeDirectory() # works3.5. Pointers

Pointers are a very basic data type of the C language. Conceptually, a pointer is a memory address that can point to an object.

In the iOS and OS X SDK, pointers are typically used as arguments to return objects by reference. As an example, the error argument of this NSData method expects a pointer that will be set to an NSError object in case of failure.

- (BOOL)writeToFile:(NSString *)path options:(NSDataWritingOptions)mask error:(NSError **)errorPtrRubyMotion introduces the Pointer class in order to create and manipulate pointers. The type of the pointer to create must be provided in the new constructor. A pointer instance responds to [] to dereference its memory address and []= to assign it to a new value.

The NSData method above can be used like this in Ruby.

# Create a new pointer to the object type.

error_ptr = Pointer.new(:object)

unless data.writeToFile(path, options: mask, error: error_ptr)

# De-reference the pointer.

error = error_ptr[0]

# Now we can use the `error' object.

$stderr.puts "Error when writing data: #{error}"

endIn the case above, we need a pointer to an object. Pointer.new can also be used to create pointers to various types, including the basic C types, but also structures.

Pointer.new accepts either a String, which should be one of the Objective-C runtime types or a Symbol, which should be a shortcut. We recommend the use of shortcuts.

Following is a table summarizing the pointers one can create.

| C Type Pointer | Runtime Type String | Shortcut Symbol |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

RubyMotion supports the creation of structure pointers, by passing their runtime type accordingly to Pointer.new, which can be retrieved by sending the type message to the structure class in question. For instance, the following snippet creates a pointer to a CGRect structure.

rect_ptr = Pointer.new(CGRect.type)Pointers to C characters, also called C strings, are automatically converted from and to String objects by RubyMotion.

3.6. Function Pointers and Blocks

C or Objective-C APIs accepting C function pointers or C blocks can be called by RubyMotion, by passing a Proc object instead.

Functions pointers are pretty rare in the iOS and OS X SDK, but C blocks are common. C blocks are an extension of the C language defined by Apple. The caret (^) character is used to define C blocks.

As an example, let’s consider the addObserverForName:object:queue:usingBlock: method of NSNotificationCenter, which accepts a C block as its last argument.

- (id)addObserverForName:(NSString *)name object:(id)obj queue:(NSOperationQueue *)queue

usingBlock:(void (^)(NSNotification *))block;The block in question returns void and accepts one argument, a NSNotification object.

This method can be called from Ruby like this.

notification_center.addObserverForName(name, object:object, queue:queue,

usingBlock:lambda do |notification|

# Handle notification here...

end)The enumerateObjectsWithOptions:usingBlock: method of NSArray presents a more complicated case of a C block, which accepts 3 arguments: the enumerated object, its index position in the array and a pointer to a boolean variable that can be set to true to stop the enumeration.

- (void)enumerateObjectsWithOptions:(NSEnumerationOptions)opts

usingBlock:(void (^)(id obj, NSUInteger idx, BOOL *stop))block;Assuming we want to stop at the 10th iteration:

ary.enumerateObjectsWithOptions(options, usingBlock:lambda do |obj, idx, stop_ptr|

stop_ptr[0] = true if idx == 9

end)(Obviously this example is used for educational purposes, in RubyMotion there is no need to use this method, because NSArray responds to the Ruby Array interface which is much more elaborate.)

|

Important

|

The Proc object must have the same number of arguments as the C function pointer or block, otherwise an exception will be raised at runtime.

|

|

Important

|

In case of a C function pointer argument, you need to make sure the Proc object will not be prematurely collected. If the method will call the function pointer asynchronously, a reference to the Proc object must then be kept. Memory management is discussed in the following section.

|

4. Memory Management

RubyMotion provides automatic memory management; you do not need to reclaim unused objects.

Since memory can be limited on iOS hardware, you must take care not to create large object graphs.

RubyMotion implements a form of garbage collection called reference counting. An object has an initial reference count of zero, is incremented when a reference to it is created and decremented when a reference is destroyed. When the count reaches zero, the object’s memory is reclaimed by the collector.

RubyMotion’s memory management system is designed to simplify the development process. Unlike traditional Objective-C programming, object references are automatically created and destroyed by the system. It is very similar to Objective-C’s ARC, in design, but it is implemented differently.

|

Note

|

Object collections are triggered by the system and are not deterministic. RubyMotion is based on the existing autorelease pool infrastructure. The system creates and destroys autorelease pools for you, for instance, within the event run loop. |

4.1. Weak References

Object cycles, when two or more objects refer to each other, are currently not handled by the runtime. It is therefore important to explicitly create weak references in this case, to avoid the referred objects to leak memory.

RubyMotion implements the WeakRef class, similar to the one in the Ruby’s weak_ref standard library. Weak references can be created using WeakRef.new(obj), and the passed object will not be retained. All messages sent to the WeakRef object will be forwarded at the dispatcher level to the passed object.

Here is an example implementing the delegate pattern using a weak reference.

class MyView

def initialize(delegate)

@delegate = WeakRef.new(delegate)

end

def do_something

# ...

@delegate.did_something

end

end

class MyController

def initialize

@view = MyView.new(self)

end

def did_something

# ...

end

endWithout a weak reference here, both MyView and MyController objects would leak memory.

|

Note

|

We expect the RubyMotion runtime to be able to deal with cyclic references at some point. Once it happens, the WeakRef class will be replaced with a no-operation.

|

4.2. Objective-C and CoreFoundation Objects

Objects created by Objective-C or CoreFoundation-style APIs are automatically managed by RubyMotion. There is no need to send the retain, release or autorelease messages to them, or use the CFRetain or CFRelease functions.

The following piece of code allocates two NSDate objects using different constructions. In typical Objective-C, the returned objects would need to be differently managed. In RubyMotion both objects will be entitled to garbage-collection.

date1 = NSDate.alloc.init

date2 = NSDate.dateIn order to prevent an object from being collected, a reference must be created to it, such as setting an instance variable to it. This will make sure the object will be kept alive as long as the instance variable receiver is alive.

@date = date1 # date1 will not be collected until the instance variable receiver is collectedThere are other ways of creating references to an object, like setting a constant, using a class variable, adding the object to a container (such as Array or Hash) and more. Objects created in RubyMotion and passed to Objective-C APIs will also be properly referenced if needed.

4.3. Immediate Types

The Fixnum and Float types in RubyMotion are immediates; they don’t use memory resources to be created. The runtime uses a technique called tagged pointers to implement this.

The ability to use these types without affecting the memory usage is important as a sizable part of a real-world app is spent in control drawing, which can make intensive use of arithmetic algorithms.

|

Note

|

Since iOS is using a 32-bit architecture, immediate types are encoded on a 30-bit pointer (we need 2 bits for type information). On OS X, immediate types will be encoded on a 62-bit pointer when the program runs on recent Mac computers, which are powered by a 64-bit architecture. |

5. Concurrency

The ability to run code concurrently became critical as multicore processors appeared on iOS devices. RubyMotion has been designed around this purpose.

RubyMotion has the concept of virtual machine objects, which wrap the state of a thread of execution. A piece of code is running through a virtual machine.

Virtual machines don’t have locks and there can be multiple virtual machines running at the same time, concurrently.

|

Caution

|

Unlike the mainstream Ruby implementation, race conditions are possible in RubyMotion, since there is no Global Interpreter Lock (GIL) to prohibit threads from running concurrently. You must be careful to secure concurrent access to shared resources. |

Different options are available to write concurrent code in RubyMotion.

5.1. Threads and Mutexes

The Thread class spawns a new POSIX thread that will run concurrently with other threads. The Mutex class wraps a POSIX mutex and can be used to isolate concurrent access to a shared resource.

5.2. Grand Central Dispatch

RubyMotion wraps the Grand Central Dispatch (GCD) concurrency library under the Dispatch module. It is possible to execute both synchronously and asynchronously blocks of code under concurrent or serial queues.

Albeit more complicated to comprehend than regular threads, sometimes GCD offers a more elegant way to run code concurrently. GCD maintains for you a pool of threads and its APIs are architectured to avoid the need to use mutexes.